• by Thomas F. Huertas, Partner, Ernst & Young

Infrastructures are integral to the financial system. They perform critical economic functions. They are hubs that allow financial institutions and their customers to make payments. They clear and settle transactions and act as a central counterparty for securities, derivatives, and foreign exchange instruments. If an infrastructure implodes, so may a market or even the economy at large.

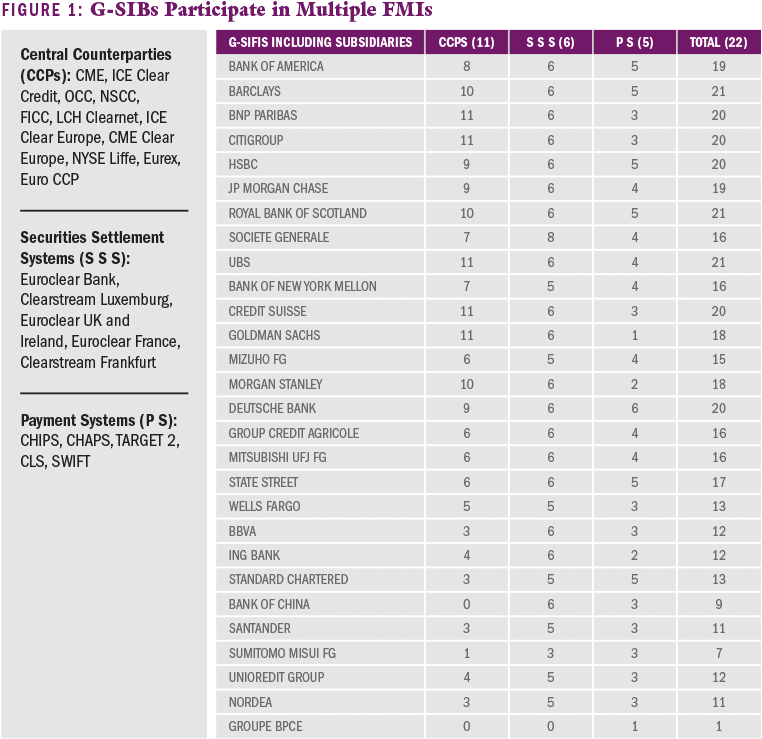

Financial market infrastructures (“FMIs”) are tightly linked with one another. If payment systems fail, securities may not be able to settle. If central counterparties fail, bilateral clearing and settlement procedures can quickly become overloaded. Infrastructures are also exposed to common risks, the most important of which are the credit or counterparty risks that come with their principal participants, global systemically important banks (“G-SIBs”). Indeed, most G-SIBs are members of many infrastructures (see Figure 1), so the failure of any one G-SIB could put many infrastructures under pressure, and the failure of any one infrastructure could put most, if not all, of the G-SIBs under pressure.

Infrastructures are by their nature systemic, and certifying continuity for them in plans for recovery and resolution is critical to sustaining financial stability. The Financial Stability Board (“FSB”) has set a standard that these infrastructures should be able to withstand the simultaneous failure of two of their largest participants.

Financial Market Infrastructures Are Diverse

In this article, I will consider four types of FMIs: payment systems, securities settlement systems, central securities depositories, and central counterparties. My principal focus will be on entities owned or operated by the private sector, as opposed to official authorities such as central banks (hereinafter the abbreviation “FMI” refers specifically to the private entities). FMIs are based in various jurisdictions, have diverse corporate structures, and have diverse business models. They incur different types of risk, and participants are subject to different degrees of loss mutualization. FMIs are also subject to varying forms of regulation and supervision, as well as to various bankruptcy and resolution regimes.

Coordination Can Ensure Continuity

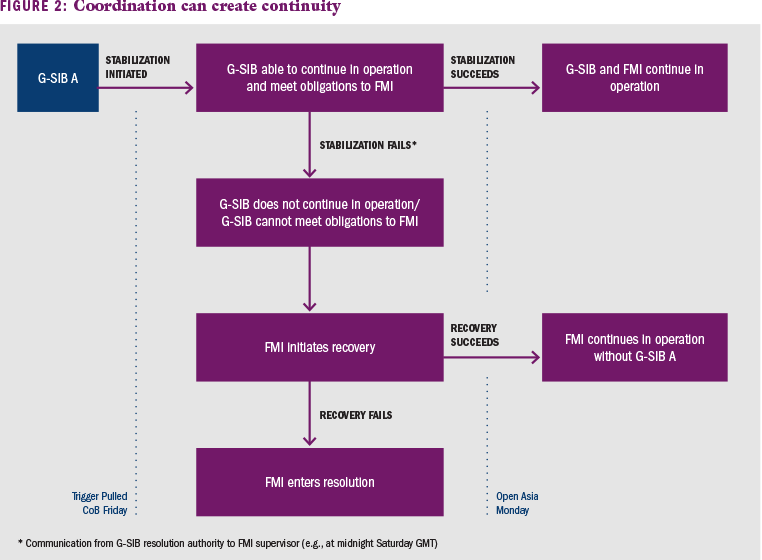

A G-SIB’s failure may threaten the FMIs in which the G-SIB participates. However, there are a number of measures that authorities can take with respect to resolving the G-SIB that would keep affected FMIs intact and in operation. G-SIB supervisors should include these measures in the cooperation agreements mandated by the FSB. FMIs, for their part, need to give resolution authorities for failing G-SIBs a reasonable amount of time to take these measures. But during that interval, FMIs should make final preparation to take recovery and/or resolution measures of their own (see Figure 2).

The first set of measures relates to the entry of the G-SIB into resolution. Its supervisor should initiate resolution at the end of the business day, when the day’s transactions are complete. This will generally be the end of the business day in the United States (as the ‘western-most’ country in which a G-SIB does business) at the start of an interval lasting a number of hours in which all markets are closed. Putting the G-SIB into resolution at the end of the business day would allow

FMIs to settle for the G-SIB’s resolution day on schedule and avoid the disruption that would occur if the G-SIB’s resolution were initiated in the middle of the business day. However, it is unlikely that resolution authorities will find it either appropriate or possible to give such an explicit assurance in advance. Consequently, FMIs should ensure that they could take steps to minimize their “exposure at resolution” to a troubled G-SIB. Depending on the structure of the relevant markets and the specific requirements of each FMI, this might entail:

- Strict rules establishing legal finality of transactions.

- Compression of the interval between trade date and settlement date insofar as appropriate for market conditions.

- Matching of confirmations and straight-through processing to ensure that all transaction instructions entering the FMI are accurate.

- Reducing settlement risk, which can be accomplished by a variety of techniques, including:

- Real-time gross settlement (used in payment systems to settle payments against cash, usually in the bank’s reserve account at the central bank)

- Real-time final settlement systems (used to describe payment netting or hybrid systems that provide for final settlement of payments without necessarily resorting to gross settlement)

- Payment versus payment (used in foreign exchange settlement systems)

- Delivery versus payment (used in securities settlement systems)

- Novation (used in CCPs where the CCP accepts transactions)

- Frequent netting of gross exposures, which is particularly effective when combined with settlement.

The second set of measures relates to minimizing loss. Coordination between G-SIB resolution authorities and the FMI supervisors confers distinct advantages, especially when a G-SIB will continue to participate in an FMI during the resolution process. In such a case, the entry into resolution would not impose a loss, either on the FMI or on the other participants.

To facilitate such an outcome, the resolution authority of the G-SIB should employ a policy of “constructive certainty.” Under such an approach, the resolution authority of the failed G-SIB should inform the market as soon as possible (ideally at the same time that it announces the entry of the G-SIB into resolution) how it intends to resolve the G-SIB. Then, supervisors of the FMIs in which the G-SIB participates should take steps to:

- Prevent the entry from automatically triggering an exclusion or suspension of the G-SIB from participation, or the imposition of losses on the failed G-SIB or other participants.

- Ensure that the FMI accommodates the ability of the resolution authority to implement a “continuity” resolution strategy by allowing the G-SIB to continue to transact.

- Confirm that the FMI is ready and immediately able to implement the recovery and resolution procedures outlined below, as soon as it gets the green light.

Recovery at the FMI, If the G-SIB Cannot Continue

If the resolution of the failed G-SIB ends its operation, the FMI would immediately need to initiate recovery procedures that limit the loss that it or other participants would incur and ensure that it can continue to perform its critical economic functions for other participants.

An FMI’s ability to achieve these objectives critically depends on the steps that it takes “in peacetime”—well in advance of participant failure. It also depends on the close cooperation between the resolution authority for the G-SIB and the supervisor(s) of the FMI(s) in which the G-SIB participates. In particular, the G-SIB resolution authority should notify the FMI supervisor(s) as soon as possible, if the resolution of the failed G-SIB will end the G-SIB’s operation. Such a notification will allow the supervisor of the FMI to give the green light to recovery procedures at the FMI.

Loss limitation—as well as its allocation—matters, because the imposition of loss from the FMI to direct or indirect participants can adversely affect their capital and liquidity. While it is important for the business models of certain FMIs that loss be mutualized, such adverse effects need to be limited, lest the failure of the FMI cause one or more of its participants to fail, and possibly set off a chain reaction that could cause the financial system to implode.

Effective measures in this area include rules to apportion losses among participants according to some type of “waterfall.” As a general principle, the first loss under the waterfall should effectively be allocated to the failed participant, and the FMI should compose its rules and conduct its risk management so that the G-SIB’s contribution to the default fund is likely to be adequate to cover FMI’s net exposure to the failed G-SIB. This loss should be calculated at the point at which the failed G-SIB enters resolution, and the supervisor of the FMI should communicate to the supervisors of its participants whether the failed G-SIB’s contribution is sufficient to cover the entire exposure, and, if it is not, the amount of loss that would be apportioned to each of the other participants and/or to the FMI itself according to the “waterfall” governing loss allocation at the FMI. However, the FMI should be prohibited from initiating the waterfall until it receives authorization from its supervisor to do so. Further, the FMI supervisor should refrain from issuing such authorization until it becomes clear that the failed G-SIB will not continue in operation (see discussion above).

Supervisors should pay particular attention to ensuring that default funds and resources of the FMI itself are liquid, so that the FMI can make any required payments to participants. If the waterfall agreement envisions replenishment of the default fund, measures in place should ensure that such replenishment could be accomplished rapidly—even over a weekend.

The ability to replenish the default fund is a critical component of any program to “reboot” the FMI so it can perform its critical economic functions for the remaining participants. If losses from the failed participant exhaust the default fund, a new default fund will be needed to support the new transactions.

The reboot program should include a process to handle “in flight” transactions involving the failed participant. This ability would be particularly important in securities settlement systems, where there is a gap between trade date and settlement date. The FMI’s recovery plan should also address any operational or service issues that may arise in connection with having to unplug the failed G-SIB from the FMI. These may be quite significant, if, for example, the failed G-SIB was providing cash management or custody services to the FMI.

Finally, the FMI recovery plan should demonstrate how the FMI would operate without the failed G-SIB as a participant. This should include both operational and risk management aspects, as well as an assessment of how resilient the FMI would be to the failure of a second G-SIB participant.

Resolution at the FMI, If Recovery Fails

If recovery measures fail, the FMI will no longer meet minimum regulatory requirements (threshold conditions). At this point, the FMI supervisor should put the FMI into resolution and a resolution authority should take responsibility for the FMI.

In cases where the FMI is structured and operates as a bank, the FMI will be subject to bank regulation and supervision, as well as to bank resolution regimes, rules, and procedures. Resolution plans for such entities should follow the same precepts as those for banks, so that the “bank” FMI is “safe to fail.”

However, for some nonbank FMIs, resolution plans may need to clarify:

- Where the dividing line between recovery and resolution lies

- Who has responsibility for “pulling the trigger” to initiate resolution

- Which agency serves as the resolution authority

- Which regime should govern the resolution

Without clarity on these key points, the failure of a nonbank FMI poses the danger of disorderly liquidation or taxpayer takeover. Avoiding such outcomes may entail changing the law, changing the FMI’s charter (so that the FMI becomes a bank and falls under the bank resolution regime), or establishing a “pre-pack” resolution process that can be triggered, if recovery fails. These changes are particularly important for FMIs for which there are limited alternatives or substitutes.

Where there are alternatives or substitutes, the resolution plan for the FMI may call for an orderly wind-down and the cessation of new activities. The rules for the FMI should include such plans and the supervisors of the FMI and participating G-SIBs should review them. The losses that a G-SIB participant might incur at each stage of the waterfall should be clearly dimensioned, and the G-SIB supervisor should check that the lower capital required against exposures to FMIs,

and central counterparties in particular, is adequate to cover the risk to which the G-SIB participant may be exposed.

If an FMI’s resolution plan envisions a shift to alternatives, the supervisors of the respective FMIs and of their participants will want to know how this shift will be accomplished (e.g., does the resolution plan envisage the transfer or novation of contracts?). Supervisors for the participants should also assess, together with the supervisor of the alternative FMI, the alternative’s capabilities to handle the rapid surge in volume that could result if participants were to shift transactions from the failed FMI. These same authorities as well as systemic risk boards will also want to assess the implications for financial markets if some participants in the failed FMI could not access the alternative.

As a final note—a statement of what should perhaps be obvious—if an FMI cannot resolve upon failure without cost to the taxpayer, or without significant disruptions to financial markets or the economy as a whole, we need to drastically reduce the reliance on it or the probability that it could fail. •